An Introduction to Gummy Films with Rachel Walden & Pauline Chalamet

Bleeding Edge gives the inside scoop on the hot new production company behind What Doesn't Float, Gummy Films.

What Doesn’t Float is an anthology of seven different stories, all taking place in a version of New York City that one rarely gets to see in the movies, on the beaches and docks and canals and edges of a city that is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean. It also brings together many familiar names from the New York indie scene, including Sean Price Williams (Good Time, The Sweet East) and Hunter Zimny (Funny Pages, The Scary of Sixty-First) as cinematographers, as well as Keith Poulson (Hellaware, We Are) and NYC filmmaking legend Larry Fessenden (Habit, Wendigo) in acting roles.

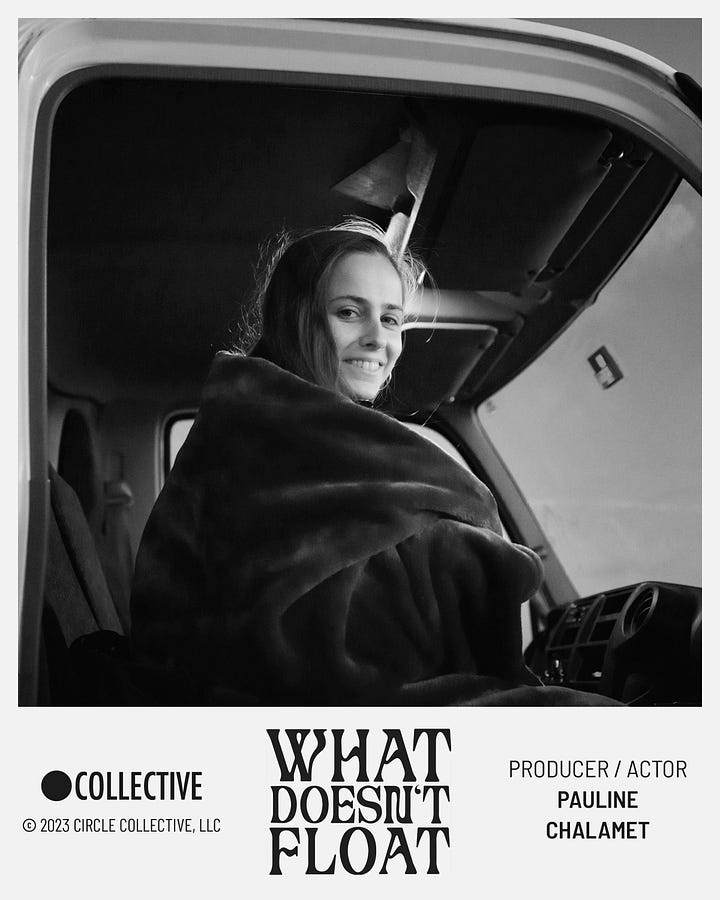

A shoot spanning multiple years, the film was a labour of love for multiple parties involved. This is no clearer than in producer Rachel Walden and co-star/producer Pauline Chalamet. Having respectively worked on Hollywood productions like Joker and The King of Staten Island in small roles, they were ready to prove themselves in a more hands-on fashion, pulling off a small-budgeted, but narratively and stylistically ambitious picture with a crew of similarly like-minded artists. Also coming off Walden’s short film directorial effort, Lemon Tree, debuting at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Gummy Films is quickly becoming a force to reckon with in a transformative time for indie film. We were lucky enough for the two burgeoning producers to join us for a quick chat.

BE: So how was Paris Fashion Week?

Rachel Walden: [laughs] You know what? I've been plus one-ing it at Paris Fashion Week with Pauline for a couple years now, and I think this was the most fun we’ve had so far. We went to Louis Voitton and the music…

Pauline Chalamet: We discovered a new favorite artist!

RW: In case she's out there listening- Pauline, I'm going to let you pronounce her name so that I don't butcher it.

PC: Zaho De Sagazan.

RW: So good. We’re desperate to make a video for her now.

BE: Oh, great. So it was a work opportunity too, going?

PC: [laughs] Oh yeah, that's our m.o.

BE: Could you two describe how you two met and when you realized you had shared interests?

PC: Well, we had met on What Doesn't Float. I had known Luca since I was a teenager and then when the project started developing, he very quickly talked about his friend Rachel, who was a producer, and he said a very, very good producer. And I was like, oh my God, great. And then I guess, I actually don't remember the first time Rachel and I met, but it probably was at Cafe Gitane or something.

RW: I think it was actually right around the corner from our now-office in Dumbo. Shauna [Fitzgerald] was house-sitting a friend’s spot above Vinegar Hill House.

PC: Oh, yes. So yes, in Devinne’s apartment. But anyway, so we met there, but then very quickly, I guess we're very lucky, right? It's only in starting to do this press that Rachel and I have started to kind of talk about how serendipitous our meeting was because we instantly got along. It became so natural, we kind of balanced each other out as producers. We could pick up where the other one left off. We understood how each other's brains worked.

RW: You know it doesn’t always work out when you try to collaborate with a friend in a creative sense. A lot of times you just don’t click with people in that way. I think Pauline and I succeeded as professional peers or colleagues so well because that’s how we were introduced to one another. We met each other in a working environment, and we understood each other that way first, and then our friendship was kind of built around that. We’re very lucky in that sense.

BE: So what would you describe as the mission statement of Gummy Films?

RW: I think that has developed over the years, and maybe still is. At the beginning, Gummy was created as a resource for our friends to make their work. It felt more like a commitment to ourselves; a push to focus on our projects as a collective of filmmakers. We were all coming from these lower level positions on bigger projects, or didn't really have our hands dirty in the scene. We really started the company as just kind of like a, let's stop fucking around and put something on the line. Let’s hold ourselves accountable for this thing that we say we want to do. I think that spirit has continued to shape the company and the projects we are attracted to.

PC: We're very focused on giving the person who's creating the idea, often the director, the power to really be in control. Obviously we want to work on projects that have bigger budgets, but I think at this stage, what we're trying to relish in is the idea that you don't have these executives or studios that kind of weigh in and have more opinions. And even when we're working on projects where we don't fully agree with what the director wants to do or how they want to do it, at the end of the day, it’s always what the director wants, it's what the creative wants, which makes for an eclectic mix of different kinds of projects. But really then everybody's learning because if you're letting people kind of go to the end of their ideas, you only advance yourself as a creator. So I think we take pride in being able to support artists who we work with, including between the three of us, how we want to do things and help push each other to really go to the end of our ideas.

RW: If we've chosen to get behind a director, then that means we respect them creatively and believe in them as an artist. So while we're a very opinionated bunch, something that we are committed to is being a very director-forward production company. We like to help people realize their ideas, but there’s nothing worse than a filmmaker’s voice being stepped on by too many cooks in the kitchen. It also makes for a really boring movie.

BE: I mean, Luca had mentioned in our other interview with him, a couple of the films Gummy had in post-production. Can you describe them further and what attracted both of you to them?

PC: Well, I was just thinking of projects that we have in post right now; we have RachelOrmont.Com. I just read this script and I was like this is so unlike anything I've read. There’s not a lot of times when we'll get a script that the three of us can get behind. We're like, oh, this is unlike anything we've read. This wants to take risks, this wants to try and say something, and not say something like a social cause per se, but try to say something cinematically. What kind of experiences and experiments can happen with the story? So RachelOrmont is a trip. We know Peter Vack certainly takes huge risks as a filmmaker and as a storyteller.

For me, it's really, I like the script or I like the story because Rachel, for instance, likes to work a lot from treatments and reading the treatment to Lemon Tree, it was like, oh, there's not a script here, but the story is clear. I find that as long as the story is clear, then we're good.

RW: When I first spoke to Peter about RachelOrmont he told me he had written it 7 years ago. The film is this kind of techno satire about living inside the internet, so it felt very of this moment. I was blown away by the fact that he had written it so long ago and just instantly believed in him from that point on. Very ahead of his time, that one.

We also have a docu-fiction hybrid feature that's in post right now, directed by Jordan Alexander. Jordan directed one of our early short films called Bubblegum And The Texas Belt Buckle and also our first music video as a company. I think once we saw how strong Jordan’s voice was, we all agreed that anything he wants to make, we're just going to get behind. This latest film, I Don’t Care About Family Anymore, was born from a documentary he started to shoot in New Orleans about a reunion between two of his estranged friends. When they were down there, Jordan started to orchestrate some beats so it worked more like a narrative feature. Then Luca started editing the film and it just left the world of documentary all together, and that prompted additional trips down to New Orleans to film more connective scenes. Now it’s just a movie with non-actors.

PC: It became a narrative feature from footage that was then cut together and it was like, okay, let's go back and get this. And then the final trip was kind of like, okay, what are the missing scenes that we need to tie this together? So a very original way of creating a movie, but a way to create a movie nonetheless.

BE: Back to What Doesn't Float, did the script have relatable themes to both of you? Could you talk about your specific relationship to New York?

PC: I mean, the script *is* the writer, Shauna Fitzgerald. If you meet her, she's sardonic, she's quick witted, she has a dark sense of humor, she is all this stuff that comes through in the stories. But I think it really represents the underbelly of New York City. And how we choose to shoot or set the stories; most of them are set in parts of New York that you don't typically associate with being parts of New York City, but that are a hundred percent New York. The beaches of Staten Island or the beaches of Brooklyn, they’re fully New York City, even on a November day. So I think that there was a very relatable kind of desperate quality that each of the protagonists of the stories share that is relatable to the essence and energy that is in New York City. I find it's a place you can so easily drown in. So I felt that Shauna did such a good job of portraying that through these different stories.

RW: I had only lived in New York for a year before we made What Doesn’t Float. I was the only one from the kind of core team that wasn't from New York. When we were trying to find money, we were pitching it as a movie about New York made by New Yorkers. I'm from Atlanta, so it was just a total lie. But I was still having a lot of experiences in New York that existed within the script of What Doesn’t Float; a lot of moments of just feeling very, not to be cheesy, but like a fish out of water. I think that level of discomfort in the city, the feeling of being thrown out there on your own, was something that I connected to at the time. I also think there's just a lot of universal experiences in the movie that have nothing to do with New York at all. How big of a deal things can be made out of something so small, what it’s like to have a disagreement with another person that is perhaps derived from pushing something down within yourself so deeply that it is creating a disconnect from others and the world around you.

BE: Rachel, could you talk about the genesis of your short film Lemon Tree?

RW: Lemon Tree is based on a true story that my grandfather actually told me about a road trip gone wrong with his father in the sixties on the way back from Disney World. I wanted to make a short about it for almost eight years before I actually shot it. Part of me was waiting for the right group of people to make it with, most of which I found through the making of What Doesn’t Float and the Gummy projects that followed. I also think I needed people like Luca and Pauline in my life to make me make it. I had been producing so many other projects at the time, the idea of directing again kept falling behind in the timeline. Finally Luca and Pauline were like, okay, we’re doing this in the fall, what do you need from us to make it happen? They took away all my excuses.

From the original story, Lemon Tree just evolved and changed based on what we had access to. Originally I was like, ok we're all going to Cherokee, North Carolina. Then we of course didn't have money to do that. Next thing we’re shooting in upstate New York. Disney World became a carnival in Long Island. The Sonic restaurant that existed in this original story became a highway diner. My friends became the characters. Most everybody in Lemon Tree, aside from Gordon Rocks, the kid, is a non-professional actor. The film just sort of tumbled into a more crafted, fictional piece based on what I had around me to make it possible. I believe that every “sacrifice” or departure I made from the original story made the film stronger in the end.

BE: And this is my final question, but it's a big one. Can you two kind of just describe the nitty gritty of what it is to produce a very small budgeted indie film?

PC: You're a professional PA, that’s what it is. You're a professional PA who also has to do all the paperwork that maybe line producers have to do. And also you're a *producer* producer because you're helping creatively, and then you're also an executive producer because you are helping find money however you can. And I think when you're a producer at the level of What Doesn't Float, you have every single job that has production or producer in it, that’s how I like to describe what it is to be producing micro budget features.

RW: Yeah, you gotta wear all the hats. You also have to be very committed to the project and to the people that you're making it with, because otherwise it can feel like an impossible task. Problem-solving is a creative, almost artistic, endeavor when you don’t have money to throw at every hurdle. So, if you don’t understand or connect to the project then you’re screwed. When you do care, both about the film and the people you're making it with, it is one of the most rewarding experiences that you can have. Filmmaking is exhausting, and sometimes even heartbreaking, but I don't think we'd pick another career if we could.

We’ll see you on Friday, October 20, at the Canadian premiere of What Doesn’t Float!